One of the main topics that Sarah McNicol highlights is the idea that reading, and understanding, comics requires a variety of literacies. Comics require the reader to comprehend and connect written text, images, blank spaces, and their own experience in order to create meaning within the novel. This also makes comics unique in their implementation in the classroom: their adaptable meanings, varied rhetorical elements, and overall reliance on the expertise of the reader makes them especially susceptible to questioning and censorship. Using the Chicago Public School’s removal of Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi, McNicol explores how a lack of training, understanding of the genre, and overall comic ignorance among public officials can lead to misconceptions and limitations placed on students’ access and learning. Neil Gaiman comments on the dangers of limiting children and students’ access to information, especially through literacy and reading. Gaiman explores the roles of libraries and librarians as preservers of knowledge culminated through time, as well as guiders of people’s retrieval and interaction with this information. Gaiman strongly warns against the dangers of not having literate children: illiteracy does not allow the exchange of ideas, the creation of new ideas, the ability to imagine and to create, and ultimately the ability to change. A future plagued by the inability to change is a future all but destined for dystopian outcomes. As Scott McCloud explores, this adaptability in the relationship between changing technologies and media, such as comics, opens the door for possibilities of expansion beyond what we know now. As he reflects on graphic art as a method of story-telling and expression throughout history, McCloud examines how styles of the art have molded and changed as the mediums they are published across similarly morph. Returning to more modern times with the dawn of electronic platforms, McCloud proposes that the infinite space provided by digital media allows for the once-again transformation of the nature of comics in relation to time, space, and navigation.

Going back to the incorporation of comics into the classroom, and the question of censorship/ removal of texts from instruction: I was lucky enough to have teachers in high school who incorporated out-of-print, unconventional, and “taboo” texts into our studies. As a learning community, my peers, myself, and my teacher would discuss and dissect these works in the context of open-minded, knowledge obtention for which they were written. These supplements to the traditional works prescribed by standards or expectations allowed my peers and I to understand and access a variety of realities and perspectives that we would not have otherwise known existed. I learned more about the world, about writing, and about my journey as a reader from these “outside” texts than the conventional ones that we studied; most importantly, I learned that there were acceptable and published genres outside of the limited scope that caters to the general education audiences. I learned that there are other possibilities that lie beyond standard narratives, repeated authors, and formulaic structures; I learned about myself, my community, and the diverse communities of the world through histories addressing what we experience, where we live, and how we compare to the lives of others. The opportunity to discover, dissect, and digest these types of text made me a more well-rounded reader, consumer, and participant in the literacy community as a whole. These are not experiences that I take lightly nor for granted, but they are possibilities that need to be more widespread across young learners.

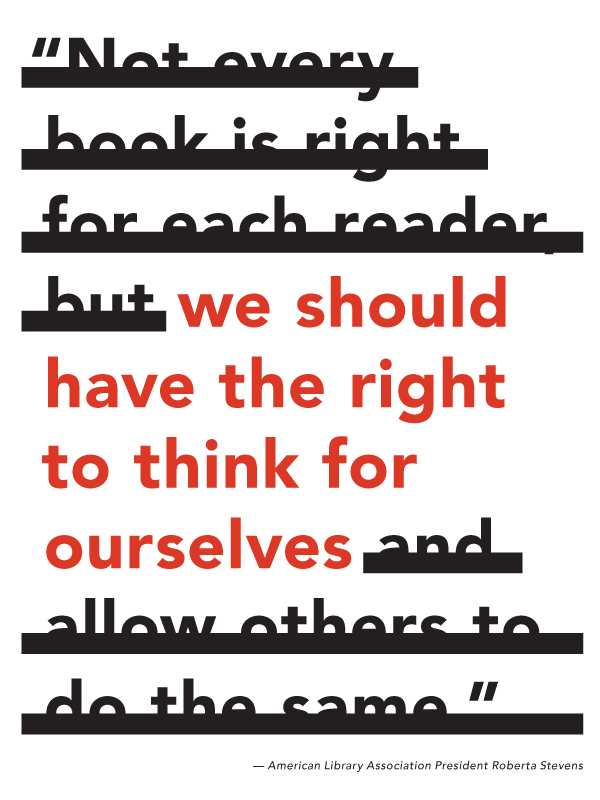

A question that I would pose to my peers would be the following: where does the line exist between protecting our young readers from inappropriate content and over-shielding them from any non-traditional literature? Where is the line between promoting protection and promoting ignorance? Is there a line, and is it our place to decide where that line is? Should the decisions be left in the hands of the administrations, the teachers, the parents, the students, the librarians, a combination of these, or none of the above?