The podcast “Manipulation” on NPR’s TED Radio Hour explores the ability of the world around us to impact people’s actions, beliefs, and memories. Four different specialists, Tristan Harris, Ali Velshi, Elizabeth Loftus, and Steve Ramirez, explore their fields through this lens, analyzing possible influences and implications of manipulation.

Tristan Harris, an ex-designer at Google, focusses on the idea that large tech companies, like Apple, Google, and Facebook are an imminent threat to our current and future society. Harris argues that technology and tech companies started out with good intentions, but soon focused instead on manipulating people’s attention, thoughts, and actions. He argues that today’s media, facilitated through large companies, is four-fold: totalizing, social, intelligent, and personalized (Harris). By using the analogy of fish swimming in water, Harris shows that today’s society is so steeped, so consumed by and in technology that we neither notice it nor can really escape it. This is especially confounded by the integration of social aspects into technology: through the recruitment and exploitation of friend membership, tech companies retain their users by acting as the conduit of conversations and relationships between individuals. Not only that, but as users tap, click, follow, or otherwise interact with the technology platforms, their overall experiences are dynamically shaped. The software monitors users’ actions and then tailors the users’ feeds to best suit what the user frequents or wants to see. Harris shows that this kind of active manipulation to recruit, maintain, and influence billions of people is not only affecting individuals, but also their relationships, conversations, values, and understandings of importance. This continues to an even wider breadth to include democracies, governments, and the gears of society as a whole.

Ali Velshi, a news anchor and host with MSNBC tackles the rising of “fake news”. As a journalist and reporter, he sees himself and others in his profession as “arbitrators”, “truth seekers”, and “advocates” for audiences; he argues that he and his colleagues seek, question, and relay reliable information as a service to the public. Not only that, but Velshi also contends that reliable news is an important check “in civil, economic, and political discourses”, meaning that it is the job of reporters and journalists to hold powers and governments accountable for their actions. Velshi continues, saying that the rise of “fake news” and “alternative facts” takes precious time, clarity, and accountability from professional, accurate news: instead of spending time and resources presenting new stories, news outlets instead have to focus on “debunking” the myths spread by “fake news”. Not only that, but “fake news” is confusing readers, causing them to question reliable news sources while simultaneously skewing their ability to critically consume news.

Elizabeth Loftus is a psychological scientist, professor, and researcher who focusses on the malleability and suggestibility of memories. Instead of focusing on the memories that people lose, Loftus focuses on the “construction and deconstruction” of memories that persist in people’s minds. Through both real cases and research experiments, Loftus shows that memories can be “distorted and contaminated” through “misinformation…if [people are] questioned in a leading way…other witnesses…and media coverage”. She highlights an example from her own laboratory where her team was able to insert false memories into 25% of a subject pool using suggestibility through a credible source (a subject’s mother) and other true information weaved into the session. Loftus points to real examples, and real implications, of false memories: over 300 innocent individuals have been tried, convicted, and served time for crimes that they did not commit due to the fallibility and malleability of eyewitness testimonies. Herein lies a second problem that Loftus addresses: people, like jurors, are convinced that memories work like a tape recorder, and thus simply because someone remembers something, it must be true. As she continuously shows, however, memories can be “controlled and altered” by both the individual themselves and the people or situations around them.

Steve Ramirez, an associate professor at Boston University who specializes in neuroscience, discusses the prospects and abilities of biological memory manipulation. Ramirez primarily sought out to investigate if he could identify and separate a memory and the emotion tied to it; since these two elements are housed in different brain areas, this would allow the individual to maintain the actual memory but not experience the paired emotional effects. To start out, however, he and his colleagues successfully located and stimulated specific memories in mice using a tiny laser; by activating a somewhat-negative memory, Ramirez and his team were able to definitively record when the mice were experiencing (or not experiencing) the behavior based on their behaviors. Interestingly, this serves as a two-way street: just as researchers were able to activate the memory, they were also able to deactivate it and return the mouse to a static state in reality. This leads to further questions about the implications of chronic stimulation, possibly pointing to therapeutic implementations. As Guy Raz brings up, however, there are dramatic ethical confounds to the ability to possibly “reactivate…erase…[or] edit” (Ramirez) memories. Ramirez emphasizes the importance of the conversations in present day to prepare for the eventual development of these abilities: “we can have this conversation now – two, three decades in advance of whenever something like this is possible in people – and when Day 0 gets there, we’ll have enough social and legal infrastructure where it’s on everybody’s minds and ideally keep it in a regulated and morally responsible manner.”

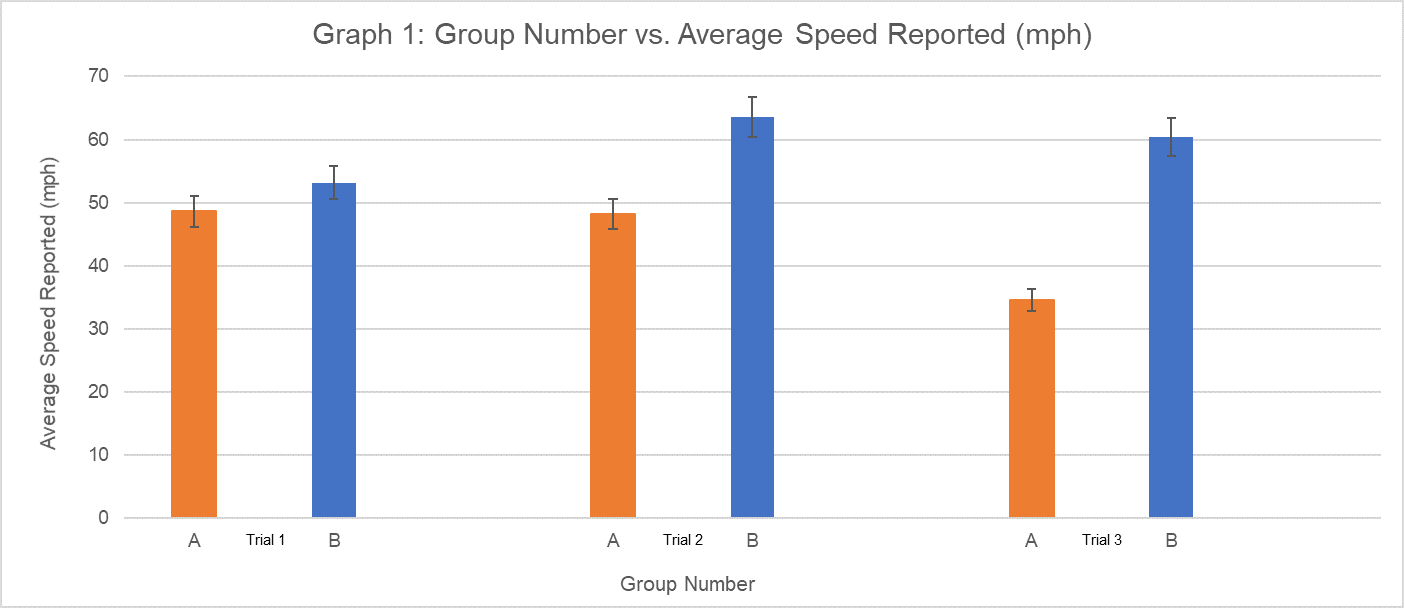

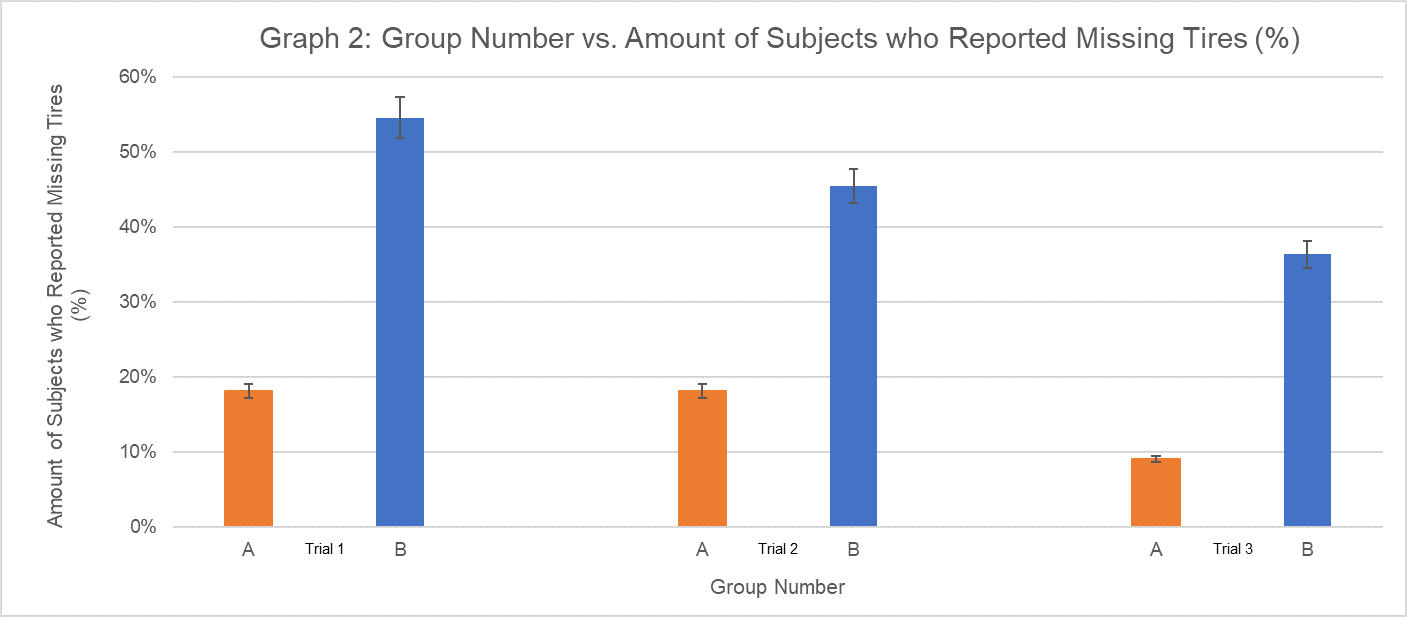

I have first-hand experience creating and assessing the malleability of people’s memories. My senior year of high school, I conducted an imitation study of Loftus and Palmer’s 1974 study “Reconstruction of automobile destruction: An example of the interaction between language and memory” for my IB Psychology course. Using three cartoon renderings of fake accidents, I measured the ability to not only influence subjects’ perceptions of what occurred in the videos, but also plant new memories of something that actually did not happen. By changing single words in sentences, or slight sentence structure changes, I observed vastly different recollections of the videos that I presented. I divided the room into two halves; one side was given relatively unbiased, non-encoded questionnaires that included the following questions:

Video 1, Group A:

1) How fast were the cars going when they hit?

4) Did any tires fall of the cars? If so, how many?

Video 2, Group A

1) How fast were the cars going when they contacted?

3) Did a tire come off one of the two cars involved? If so, how many?

Video 3, Group A

1) How fast were the cars going when they tapped each other?

5) Were any tires lost during the car accident for either car?

The other side of the room were given the altered and encoded questionnaires, which read:

Video 1, Group B:

1) How fast were the cars going when they collided?

4) How many tires came from each car?

Video 2, Group B

1) How fast were the cars going when they smashed?

3) How many tires came off of each car?

Video 3, Group B

1) How fast were the cars going when they rammed into each other?

5) How many tires did the cars lose after the car accident?

It is important to point out that all of the subjects were in the same room, the same grade, the same class, and were showed the video at the same time; even with all of these similarities, there were still drastic differences in their responses. I asked a series of six questions, but the greatest differences came in the subjects’ estimations of speeds and recollection of tires coming off of the cars. By manipulating words related to speed, such as “hit” versus “collided”, “contacted” versus “smashed”, and “tapped” versus “rammed”, Group B (the encoded group) reported speeds an average of 15.3 miles per hour faster than Group A (the control group). Simply through the powers of suggestion in Group B’s questions, I saw a 300% increase in the false recollection of tires coming off of the cars, even though this was not present in any of the videos.

A question I would pose to the class would be the following: is there any way for us to prevent fallacies in the memories of eyewitnesses and their testimonies? Should eyewitness testimonies still be used as credible evidence in criminal proceedings given, their malleability?