Kellner argues that media education and media literacy is not a debate of “if critical media literacy should be taught, but instead, how should we be teaching it” (2). In a time where children are targeted in and consumed by the digital world, Keller continues, our education system needs to take a similarly-digital focus. There is not much keeping children from technology; pretending it does not exist forces our children to venture into the expanse without proper tools. It is our job to tailor students’ educations to these necessary skills just as we do other, more traditional skills. Kellner investigates the philosophies and credence of four distinct approaches to media literacy education.

The first approach is shaped by protection: this philosophy “comes out of a fear of media and aims to protect or inoculate people against the dangers of media manipulation and addiction”. In essence, individuals argue that media has a tight grip on and influence over youth; as such, it is our job to shield our children and society by teaching protectionist media literacy. Kellner quickly contrasts this viewpoint by arguing that this drastically “over-simplifies” (2) the goals and impacts of technology and media. Taking a confrontational approach squanders any opportunity for critical comprehension, empowerment, and understanding of the “interconnections between information and power” (2).

The second approach presented by Kellner centers around the intersection between media and art. This philosophy, Kellner argues, given students an area for digital self-expression and encourages students to appreciate the “aesthetic qualities of media” (3). However, Kellner cites a subsidiary issue with this approach: “we have concerns with the media arts approach that favors individualistic self-expression over socially conscious analysis” (3). He argues that simply observing and producing through imitation in the digital landscape is not enough. Instead, students need to interact and critically engage with the content published in order to foster deeper understandings of social implications. When art media education moves beyond the surface and into “cultural studies and critical pedagogy” (3) centering on pertinent social issues, the door opens for great potential.

The “media literacy movement” (3), the third approach Kellner details, focuses on applying classic tools associated with print media to digital media. This perspective allows educators to remove subjectivity and act as conduits of information instead of critical questioners. As the most widespread approach across the US, Kellner states that “the media literacy movement has done excellent work in promoting important concepts of semiotics and intertextuality, as well as bringing popular culture into public education” (4). Despite these positives, Kellner repeats his criticism reflected in the previous two approaches: this philosophy does not encourage nor endorse the critical analysis, reflection, and empowerment of youth when interacting with media.

Naturally, Kellner’s fourth and personal approach embodies exactly this criticism: “critical media literacy…focuses on ideology critique and analyzing the politics of representation of [social issues] …incorporating alternative media production; and expanding textual analysis to include issues of social context, control, resistance, and pleasure” (4). In this way, Kellner’s pedagogical philosophy incorporates elements of the previous three approaches but does so through a lens of criticality, awareness, and deeper understanding. Critical media literacy also weaves in the perspectives of not only the producer and the students as consumers, but also the impacts upon secondary and tertiary audiences or issues. Summatively, these elements harmonize into a holistic, analytical, and conscious method of media literacy that equips students for “democratic social change” (4).

This social change arises through not only the critical analysis of media, but also the “production of alternative counterhegemonic media” (4). This means that students must not only be able to interpret media, but also challenge the images or themes expressed; students are empowered and equipped to both contest the dominant ideologies and then create contrasting media. This is especially true for individuals or messages who are consistently marginalized or misrepresented in mainstream media; teaching students to recognize and confront these themes is crucial for social progress. As Kellner discusses later in the article, “combining the analytical skills to deconstruct mainstream media with the artistic and technical skills to construct alternative counter-hegemonic media becomes a natural process” (8).

For Kellner, part of this social process includes the idea of “radical democracy” (5), or the idea that increasing communication about and through media across a society, especially among youth, will “enhance democratization and civic participation” (5). In essence, teaching students skills of comprehension and creation will incite increased performances of citizenship; such increase will further democratization and social engagement both inside and outside of the classroom. Part of challenging the dominating powers in society include challenging the domination of the teacher as a power in the classroom. As Kellner suggests, teachers must “[share] power with students as they join together in the process of unveiling myths, challenging hegemony, and searching for methods of producing their own alternative media” (6). Entering students into the equation of classroom dialogue and instruction is not a new concept; it is imperative that teachers practice their lessons of challenging dominative authority as much as they empower students through their messages.

Kellner’s approach also incorporates and addresses issues of cultural education: a “framework of conceptual understandings” (7) that weaves media, production, social realities, representation, and criticism into a cohesive educational direction. Not only that, but both cultural education and media literacy, especially as lenses towards one another, actively involve the student in educational discourse. Eventually, this leads to the students’ self-sufficiencies and independence in critically approaching media, further stimulating democratic progress and cooperation.

This reading and its concepts remind me of our Further Oral Activities (FOAs) that my peers and I completed in eleventh grade IB English. Our FOAs revolved around taking a piece of media, anything from text to podcasts, videos to picture-based publications, analyzing our selected media, and then investigating how the themes expressed in our media related to other aspects of our society. Our analyses were in part based on the language that was used throughout our selected media, but also other facets of design and implicit creators of meaning: colors, chosen target demographics, and congruence between audience and message. Though the individual production aspect of our FOAs were not as explicitly socially-conscious and widespread as Kellner encourages, we delivered oral and visual presentations to our classmates about the topics we had researched. In this way, our FOAs mirrored Kellner’s suggestions of empowering students as teachers; I would also argue that though it was not to the extent that Kellner described, our projects fostered increase social awareness among young individuals.

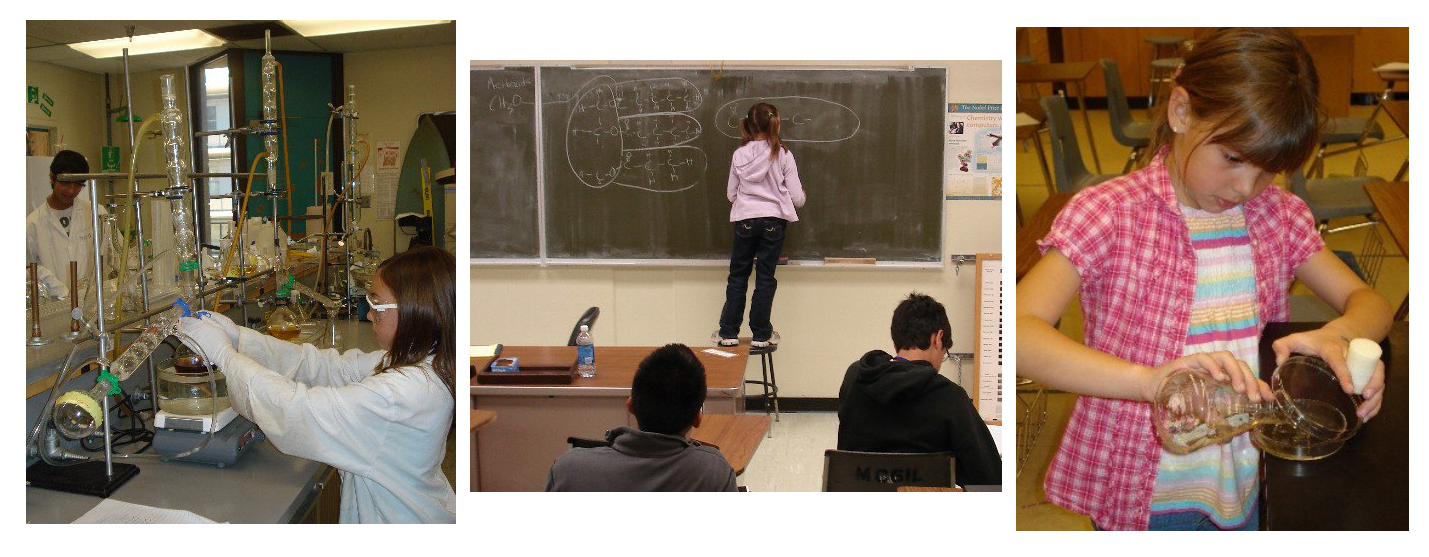

My specific FOA was centered around the effects of advertising colors and designs on the enforcement of gender stereotypes and roles onto children. I briefly discussed this in class the other day; based off of Jean Kilbourne’s Killing Me Softly 4 and the Representation Project’s The Mask You Live In, I investigated the perpetuation of gender categorizations and expectations through product marketing and advertising. Through LEGOs and NERF, I demonstrated that toy companies skew their product designs towards certain societal genderizations, insinuating that young boys must take on one set of characteristics while young girls must take on another set of characteristics. One of the most exciting parts of this project was that I was able to use myself as a counterexample: I grew up participating in activities that many deemed “not normal” for my age and gender. My childhood best friend and I preferred to climb trees, play with NERF toys, and make up tricks on our scooters and bikes instead of playing inside with his older sister and her toys. When I was not with my friends, I would prep and perform labs in my father’s classroom, doing everything from bacterial transformations to gel electrophoresis. As I got older, I began working in research laboratories at UCSD, teaching high school students about algal biofuels while simultaneously creating and analyzing samples of my own. Throughout these experiences, I learned first-hand to critique and challenge the expectations propagated by the media around me. My hope is that students across the nation are able to learn similar lessons and skills, hopefully altering the current media hegemony.

My question to the class would be the following: in your classroom, how would you facilitate critical media literacies for your students? Would you employ individual projects, class discussions, “I do, we do, you do” scaffolded activities, or something different?

Cover Image Credit: ITB: Nosso Blog. (2019). QUER SABER QUAIS SÃO AS TENDÊNCIAS TECNOLÓGICAS PARA 2019? [JPG]. Retrieved from https://blog.itb360.com.br/tendencias-tecnologicas-2019/.