Darnel Degand’s 2015 article investigates the complex interactions between social skills, community prejudices, media experiences, and teenage interests. Through a 12-month case study of two Haitian-American male teens living in New York, Degand explores the intersections between the teens’ perceptions of general success as well as social success, finding that this distinction yielded two, somewhat-different answers. For example, Narim (Degand’s first case study) defined success with a large monetary catch. On the other hand, Narim’s idea of social success was not as governed by finances, but more by the completion of personal goals and maintaining an overall approachable character. Mathieu (Degand’s second case study) mirrored some of Narim’s sentiments; Mathieu “held a holistic view of an individual’s social success that frequently involved not only having the means to live comfortably, but also having the ability to experience happiness in your life with others” (Degand 886). Also similar to Narim, Mathieu defined generic success as having a financial component, judged by an individual’s “business suits, financial acumen, and personal possessions” (Degand 886). Degand also found that Narim’s personal career goals were closely similar to the kinds of media he consumed. For example, Narim discussed a possible comedic career, while citing some of his favorite media as specials by Dave Chapelle and Kevin Hart. Mathieu discussed a future goal of being a professional soccer player, and like Narim, some of his media interests followed suit: he often researched different soccer tips, tricks, and advice on his free time. As Degand further explored, Narim and Mathieu were also influenced by the adults and family members around them, showing that the shaping of teens’ interests is a complex system. Degand stresses that individuals’ interests are a conglomeration of peer feedback, familial feedback, personal hobbies, and media mixed with the development of both academic and social skill development. As Degand states towards the end of the article, “cultures, belief systems, organizations, and individual personalities all influence success, what is defined as success, and the ability to achieve success” (Degand 894).

Constance Steinkuehler expands on this idea that individuals’ personal interests guide the types of media that they consume. She argues that media, specifically video games, “are just an easy context to look at what it means when kids actually are engaged and care about the subject matter”. Steinkuehler found that students, especially teen boys, struggled with literacy when it came to the prescribed curriculum of traditional classrooms. On the other hand, they excelled at (and, more importantly, were excited by) video games. Through the simple actions of sitting and playing with the teens, what Steinkuehler “resourcing” the teens, she discovered that she could weave literacy elements into the games that the students were interested in. Not only were the students interested in the texts, but Steinkuehler saw a drastic jump in their literacy levels: “For example, we had a reader that was in tenth grade who read at the sixth-grade level, was not faring well in school. I handed him a fifteenth-grade level text from the game and he’s reading it with absolutely fine comprehension, 94- 96 percent accuracy.” Steinkuehler continues, suggesting that ‘we forget it in schools all the time that if you care about understanding the topic, you will sit and work through, you will persist in the face of challenge in a way that you won’t do if you don’t care about the topic.” This pedagogical reversal is counter how mainstream classrooms are run, but Steinkuehler posits that changes to this system could yield great improvements in student literacies and success.

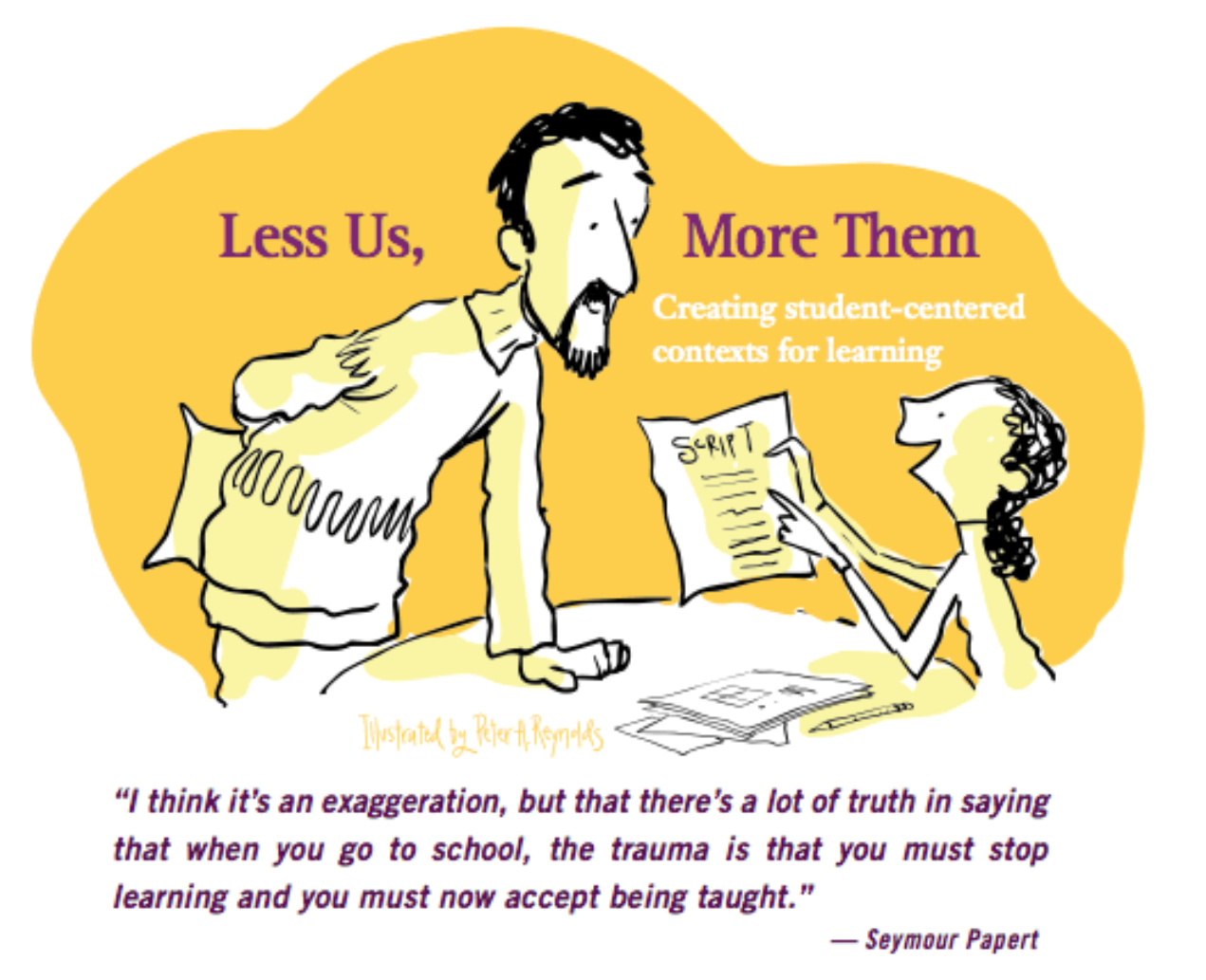

The part of these investigations that really stood out to me was actually Steinkuehler’s concluding statement: “teaching would look a lot more like community organizing where the first question is, “What do you as a community want to accomplish?” And then your job is to figure out, how do I marshal resources to help you accomplish that and along the way to tool you up with practices, knowledge, dispositions, that you keep for a lifetime.” This immediately rang bells of Montessori methods and other student-inquisition-driven pedagogies that are beginning to surface on a more widespread basis across the education system. This approach to teaching is not new, but the speed and pervasiveness of these philosophies in more classrooms is rising at a new and exciting rate. Instead of stressing student “robots” who conform to a single modality, a single set of standards, a single assessment strategy, and a single outcome, the education system is coming to terms with the reality that the post-education world is not driven by “followers”. Instead, the modern corporate world is pioneered by thinkers, by challengers, by questioners: individuals who see the status quo and choose to reimagine new realities. As such, the education system must adapt to produce more self-sustainable, self-driven, and aware individuals who can draw from a variety of experiences, perspectives, and literacies. This must be facilitated by individuals’ education, hence the rise in classrooms driven by the interests of students, as Degand and Steinkuehler comment on in their own ways.

A question I would pose to the class is the following: if you were a teacher in a K-12 classroom, what is an example of an activity you would use to encourage and foster students’ interests?

I would give them a project where they have to develop some form of media that demonstrates their interests. For example, a student loves watching YouTube videos, they can create a video that is correlates with the videos they watch. If they like watching vlogs or people cooking, they can do that. Another example can be that a student loves art, they can draw or paint anything they want.

LikeLike